Dr. Diane Menzies

Francisco Caldeira Cabral : Festina Lente

Introduction

I come here today as the current president of the International Federation of Landscape Architects to pay tribute to the life and work of a former president of the Federation, Francisco Caldeira Cabral.

Voyage of discovery

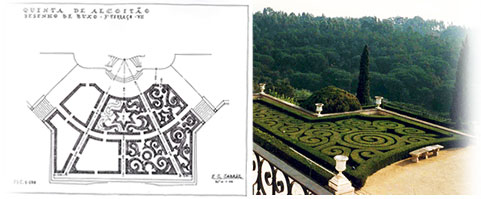

Sadly, I never had the chance to meet him. So in preparing to speak to you, and in preparing an international tribute from the organisation, IFLA, that he devoted so much time and energy to, I have had myself to go on a voyage of discovery, as I have sought and found information about Professor Francisco Caldeira Cabral’s life and his work. I have read the work of Teresa Andreson, and her research on his early career as a student at the Higher Institute of Agronomy (ISA), his studies in Berlin as World War two was brewing, and his early and largely uncredited work on the National Stadium in the Jamor valley. I have called upon IFLA archives, some of them stored in old apple-boxes which journeyed from Lisbon to Versailles and on to Brussels, and are now undergoing indexing. I have also read articles he wrote in English. I have read of the deep impact he had on students, particularly the words of Maria Celeste de Oliveira Ramos, and one of the cadre of students who travelled extensively with their professor. The picture that emerges is of a man who was multi-lingual, multi-talented, a constant traveller and an eternal student. He was not only clever, but also wise. He had a motto of “Festina Lente” – “Make Haste Slowly”, but was a fast driver, driving with students around the landscapes of Europe and Africa, sometimes en route to IFLA Congresses. Travel for him was not an experience of airports and planes, but more an expedition across motorways and up rivers. In my own journey of discovery into the life of Cabral, I have reflected on the changes that the world has seen since he started practising landscape architecture in Portugal, the things that are different now from what they were, and the things that are the same. Some of the challenges may seem new: globalisation, sustainability, security, but they have old roots. Cabral was speaking and writing about challenges 40 years ago, about the manifold challenges a landscape architect faces in landscape design, and the breadth of skills required to meet those challenges, but the principles and practices he advocated remain good to this day.

Art, Science, Spirit

As I travel around the world attending landscape architecture conferences I often find myself quoting the founding president of the International Federation of Landscape Architects, Geoffrey Jellicoe, a great friend of Cabral, who described Landscape Architecture as the “most comprehensive of all the arts”. Another contemporary and great friend of Cabral’s, Sylvia Crowe, considered it a bridge between art and science. Cabral himself was convinced of the importance of education in science as well as arts – hardly surprising given that the first landscape architecture course in Portugal was an optional course on top of the studies in Agronomy at ISA. He thought Landscape Architects needed to have a grasp of geology, ecology, climate science, of agriculture, as well as architecture, physics and fine arts. But all the knowledge in the world is not enough if a landscape architect is not able to really look at a landscape, to see the layer of history, of geology, of human use, and to discern the way it lives and sustains the lives of those who have sprung from and passed through it. Professor Cabral taught his students to really look at landscapes – The Auto del Strada in Italy, a mangrove swamp in Mozambique, or “ a village clinging to a mountainside.” As I prepared for this speech I have been reminded that of the third element that the great landscape practitioners bring: there is science, there is art, and there is also spirit, and I will say a little more on that later.

Career review

But first, it is timely to review Cabral’s career, and the eras in which he lived. I do not want to make this speech a recitation of facts and figures, but it is useful to get a flavour of the times. Cabral was born in 1908, here in Portugal. A century ago, the world was a very different place, and his lifetime encompassed huge changes: two world wars bringing upheaval over Europe, huge political changes in Portugal, and great advances in technology and increasing globalisation of industry.

Birth – discovery of the profession

In 1908 when he was born, and in 1936 when he graduated from the Higher Institute of Agronomy there were no Arquitectas Paisagista in Portugal, nor, for that matter were there landscape architects in New Zealand. Indeed, it was not until he read what he described as a remarkable article in the latest edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica in 1935 that Cabral discovered the profession that he would end up devoting his life to. I mentioned earlier the rapid technological changes. It is interesting to reflect, that in 1935 the Encyclopaedia Brittanica that Cabral read probably took up a dozen or more printed volumes. It now can fit on one Compact Disc. Those of you who brought your iPhones to this event can probably access it via your mobile browser. Having read about Landscape Architecture in the encyclopaedia he was funded by Lisbon Town Council, to study in Berlin at Friedrich Wilhelm University. There he began as a labourer in a nursery, before entering the university to learn the theory and science, in conjunction with artistic training in drawing, water-colouring, perspective, history of garden art and architecture. While still a student, he was asked to review the then plans for the National Stadium. From what I can gather, two firms of architects had each drafted plans, for great monumental stadium, located in the middle of the Jamor valley, with straight avenues to be imposed on the landscape. The design they produced reflected the grand ambitions of many politicians around the world in that period – massive, monumental stadium that dominated the landscape and proclaimed their presence. There was a strain of architecture then and there remains a strain now, of those who seek to build a monument, to design and build an intervention that dominates the landscape. We see it today, in places like Dubai, where architects and billionaires seek to build progressively more spectacular edifices – each taller and more spectacular than what has gone before. On a lesser scale, we see it too when kitset designs are laid out, buildings imposed with scant regard for the existing streetscape or local conditions. We see it when a designer is carried along by the brilliance of an idea, becomes entranced by the possibilities of a particular form and builds it, without regard for practicalities or for the local people around the site. However, more often we are working in multi-discinplinary groups, each contributing their understanding of landscape, design and community to reach an integrated and sympathetic solution which has harmony with landscape and the desires of local people. In 1937 Cabral, as a young student was asked to review the plans for the proposed National stadium to be located in the Jamor valley. The plans he received were of a grandly ambitious plan for a monumental stadium, located in the middle of the valley, a pet project of prominent politicians. Cabral reviewed the site, its characteristics and its prevailing winds. As he was later to teach his students to do, Cabral really looked at the landscape in all its aspects – the geology, the terrain, the prevailing winds, which led him inexorably to the conclusion that the proposed designs were badly flawed. His opinion, was cautious, but “clear and extremely devastating” , the avenues would cause a wind tunnel, the designs were disproportionate and the great stadium itself was sited where the Jamor river wound its way through the valley, a flood plain. He returned to Germany and sought help from his professor Heinrich Wiepking-Jurgensmann, and also worked with Konrad Wiesner, Together they suggested a more sensitive solution – less grandiose, but more elegant, a stadium nestled into the side of the valley with panoramic views across it to the villages on the other side a flexible, practical, elegant and responsive solution. I doubt that the young, not-yet-qualified landscape architect, endeared himself to the architects involved when he pointed out the flaws in the design. There is a suggestion he may have been unpopular in political circles as a result, and he was removed from the stadium project, and was not credited for the outcome. But it was the right thing to do.

Ethics - Stewardship

Speaking truth to power is seldom easy. Sometimes, however, it must be done. I often talk to students of Landscape Architecture about our ethical responsibilities. We are stewards of landscape. We owe a duty not only to our clients who commission us, but also to the people who live in an area, those who will use it in the future, and to the land itself. Cabral may have been removed from the stadium project, and others, notably Miguel Jacobetty Rosa are credited with the design for the stadium Tribune, but the final result draws on Cabral and Wiesner’s work. The final stadium seems very simple, almost obvious and natural. Its shape, draws on the traditions of the Greek amphitheatre, yet is very much a response to the Portuguese environment, and crafted of Portugese stone, albeit overlaid with plastic seats these days. What is striking is how well it has endured, while elsewhere in the world the giant stands of contemporary football stadia – some of them much younger - have crumbled and succumbed to the wrecking ball.

Anticipated Design with Nature

In paying close attention to the curvature of the land, and proposing a design that is sensitive to its features, he anticipated the work of Ian McHarg, who wrote the seminal work Design With Nature, a book Professor Cabral was later to recommend to his students. I will return to again to this theme: In his teaching, Cabral frequently anticipated major writing in landscape architecture. He was connected to the great landscape architects of his day, was influenced by them and in turn influenced a generation – both here in Portugal and across the world.

Starting at Isa.

But, back in 1940, there were no students. Having been removed from the stadium project Cabral returned to Portugal and began teaching Organographic Drawing at ISA. He took over the ISA gardens and began preparing an Independent Course in Landscape Architecture beginning in the second year of the General Course of Agronomic and Silvicultural Engineering. It cannot have been easy, in those early days, when the students studied in their spare time and he was the only teacher, but he persisted, and in doing so prepared a whole generation of Portuguese landscape architects, who, with Cabral initiated a new attitude towards urban public spaces, landscape planning, landscape restoration and protection. In 1951 Cabral became an individual member of the International Federation of Landscape Architects, one of the first to do so after its founding members met in 1948 in Cambridge and founded the Federation. The founders’ aim was international communication to promote high education and technical standards, to facilitate the sharing of information, so that landscape architects in different countries could learn from each other. Within Portugal, Cabral had similar goals when he created the Research Centre in 1953 which became the visible face of new profession. Out of this came the Portuguese Association of Landscape Architects APAP of which he would eventually become president in 1988. But before he was president of APAP, he was president of IFLA, its fifth in 1960. At his speech when he assumed the presidency at the IFLA congress in Haifa in Israel that year he spoke of IFLa’s early years as dedicated to consolidation. He referred to the period between 1951 to 1960 during which Germany, the USA and Japan joined the federation as one of development. His own presidency he saw as being one of stablisation and expansion. We have certainly expanded since – now more than 70 countries are represented in IFLA. To support that expansion, projects were begun under his Presidency to agree a standard translation of technical and terms. His own facility with languages (he seems to have spoken French, English, German in addition to Portuguese) must have helped, and it must have helped the different elements of IFLA communicate with each other. In preparing to talk to you I have had the chance to go back over IFLA’s records, and see that, as the landscape changes and goes through cycles of growth, decline and rebirth, so too does an organisation. 46 years on from Cabral’s presidency, IFLA has been through more development, expansion and need for stabilisation. Like the life of a landscape, the life of an organisation goes through cycles.

Challenges facing IFLA today : Education

In our current cycle we face two challenges in particular: education and recognition. The foundation of any profession is education in a common body of knowledge, a commitment to ongoing learning and research, supported by strong leadership from professional associations. Cabral set the groundwork in Portugal, in education, in research and in leadership and many others have continued on the path he set, as many of you are here today. I congratulate you on your work. Given the challenges and opportunities, a landscape architect’s education needs be varied, rigorous, and ever continuing. As we practice we need to be alert to changes in technology, climate and social conditions, while retaining our passion for the profession. The work is not only technical or artistic, we also need to work with and respect a range of communities and to take culture into account. The challenge of educating enough landscape architects, to a high enough standard to meet the worldwide demand now and in the future is an ongoing concern for the Landscape architecture profession around the world. In some areas, it is the biggest challenge we face. Demand for landscape architects is growing so rapidly that it is exceeding supply in many parts of the world. In China, Russia, and the United Arab Emirates booming development, the rapid middle class expansion and increasing levels of disposable income are driving demand, whereas in USA and the UK more practitioners are retiring than students are entering the profession. Africa has particular shortages: there are very few trained landscape architects available and even fewer local university courses. In South America and some areas of the Middle East there are similar challenges: too few university courses and a very limited basis for setting reliable benchmarks. To address the shortage of trained staff, consultant firms seek trained landscape architects from wherever they can source them in the world. Anecdotal information from the USA and Russia is that those who need the services of a landscape architect, and cannot get one, will chose the next best skills available. The alternative people chosen may have very little training. This leads to the risk that clients become dissatisfied with the outcomes and the reputation of the profession is affected. In some countries, education of landscape architects does not meet basic standards and graduates who emerge find they lack the skills and knowledge expected of them. Some universities are not keeping pace with improving technology or societal changes, let alone responding to global issues like climate change. To meet the burgeoning demand worldwide we need to attract good students into recognised landscape architecture programmes, as good as the ones here in Portugal, resulting in qualifications transportable across nations. The project sponsored by Cabral during his time as president, to provide a common understanding of professional terms was an early step towards transportable qualification and an international audience. A step further along that path is the recently-approved accreditation guidelines which all IFLA regions are supporting. All member associations are encouraged to undertake accreditation of their universities so that there is a sound benchmark for education standards throughout the world. The accreditation guidelines include standards that courses should meet, procedures for accreditation, a system to indicate accreditation status, and how the university accreditation would operate financially. They also make provision for courses to be accredited in different categories. From this start professional registration schemes will be developed. IFLA has taken this initiative as a means of responding to globalisation pressures, which are apparent throughout the world, and of which I will speak more later. Here in Europe EFLA takes the lead in accreditation and I know you strongly support that leadership. Linked into the issues of education is that of recognition of the profession. It may seem a paradox, but at the same time as we face a world-wide shortage of landscape architects, in some countries landscape architects struggle to be recognised as a separate profession from architecture. I do not know why this is. At an international level, there is no confusion. The International Union of Architects (IUA) agrees that the professions are separate. The occupational classification system maintained by the International Labour Organisation, as a base for collecting statistics about occupations, has long recognised Landscape Architecture as a discrete profession, although its current description is quite out of date. International Federation of Landscape Architects has provided the ILO with an amended description which reflects more accurately the modern scope and nature of the work of a landscape architect, and we expect it to be promulgated later this year. The reason the ILO identifies and categorises occupations and professions, is to provide guidance to member countries of the UN, support statistical analysis and enable labour portability – the movement of qualified professionals around the globe. In short, they support the beneficial aspects of globalisation.

Globalisation.

I mentioned earlier that Cabral’s life spanned an era of unprecedented change and social upheaval, along with increasing globalisation. Some would say Globalisation has been with us for hundreds of years, and that it began in Portugal, when Portuguese sea voyagers launched the great age of European exploration, sailing off around the globe. The Portuguese Thassalocracy was a great sea-empire stretching around the globe from North Africa to South America, and around India to Macau. Wherever and whenever it began, globalisation is a modern reality, and has many effects, features and forms. We now have a globalised market for services, like that of landscape architecture, but also for resources. We are moving to a globalised market for property which means that holiday homes in one country become affordable to residents in another. The cheapness of air travel accentuates this trend. I am sure you are aware of the effects, living as you do in a country whose sunshine and spectacular scenery attracts holidaymakers in their droves. These “wild ducks” can bring resources for the local economy, providing a livelihood for some. But property prices are also affected, as is the streetscape. Children of residents may no longer be able to afford to live in the place where their family has lived for generations. Their main street can come to look like a hundred other tourist towns – the same brands, the same shops. Traders, and property developers respond to money on offer by building short-term solutions and targeting tourists. In the process, something of the character of the landscape can be lost.

Cathedral Square : Tourism and Locals

My own home city has struggled to maintain local identity in Cathedral Square. The square sits at the intersection of roads from which spreads out the grid of the central city. In times gone by the Cathedral Square was the heart of Christchurch, a gathering place by day and night. People do gather there still, on special occasions like New Year’s Eve, or Anzac day when those who served the country in wars are remembered. But for the rest of the year, in its every-day life the demands of the dollar has seen a shift towards shops geared for tourists. Ringing the square now are hotels, banks, souvenir shops, internet cafes, restaurants, a tourist information centres and cafes with a mainly tourist clientele. Yes, there is even a Starbucks – one of the chain of coffee shops rivalling in its “café ocracy” the Portuguese thassalocracy of old. It was once possible to travel around the earth stopping at Portuguese ports along the way. These days, the port for the weary traveller takes the form of a chain-store café. It is possible to walk into the same chain in Madrid, Seattle or New Zealand and see much the same bar design, the same coffee and the same comfortable chairs, where weary travellers can sit down and open a computer and get wireless access. I understand Lisbon is next on Starbucks’ list! For some, this is a refuge from culture shock, a place to check e-mail and a home away from home, a place to connect and restore. However, the paradox of globalisation is that one person’s home comforts can take over another’s landscape. The problem is not new. Cabral himself, in writing of the need for “the Manifold Landscape Design” looked at the challenges of planning a new road system and the need for landscape not only to serve “big town people” who are moving at lightning speed from one town to another, but also the country people, who while they may sometimes need the roads, also need a safe environment, without excessive noise or pollution. There is an upside to globalisation, as is the chance we get to connect with people around the world, to learn from each other, to discover new solutions to challenges like climate-change. And one of the things we learn is that, everywhere, people face similar challenges, and have similar needs, both on a physical, but also on a spiritual level.

Landscape and Spirit.

We all have a need to belong somewhere, to feel a sense of connection to a place, to the earth, and to each other. In the short term, the culture-shocked traveller can find a nest in a wi-fi connection on their iPhone and some familiar fast-food, but we each need more than that. We need to belong, to feel nurtured and sheltered. We need a sense of perspective and place, the chance to be aware of the passage of time and of the seasons. We need public spaces, which encourage people to connect with each other, in person, and not just via an electronic connection.

Whakapapa

In the spirit of globalisation of ideas, I would like to share with you some of my own heritage, and along with it a concept feel sure Professor Cabral would have intuitively understood, the concept of Whakapapa. In Maori culture, in New Zealand, land is not seen as a possession, but as a living thing, an ancestor. Land does not belong to people, but people to the land. In a traditional Maori setting I would introduce myself by first telling you of the land – the mountain, lake or rivers that I belong to, my home marae, and then I would tell you my ancestors before coming to my own name. This process, called whakapapa links the layers of my identity and culture, and is an important part of a Maori person’s identity. Maori are not alone in this. Writing in the 70s, Tuan in coined the term “Topophilia” to refer to the emotional ties people have with a landscape. He defined the term as ‘the affective bond between people and place or setting’ . the affective ties being with the material environment. He said that it was “practical to recognise human passions” in designing a landscape. And 25 years before Tuan was writing, Professor Francisco Caldeira Cabral was inspiring his students to think in a similar way: Maria Celeste de Oliveira Ramos has said of Professor Cabral, that

“the way he talked made us feel… the sacredness of the earth and of the life it contained, revealed in so many different forms where Man was merely the administrator and the guardian. He also made us think and feel that men are all part of that same life, of the same planetary ecosystem at the top of the food chain, filled with life and with a sense of sacredness, as was wild life and human life, the only difference being that we were aware. I had never until then heard anyone say that human beings were a link in the same ecosystem of the Earth.”

This concept, of being connected to the land and needing to care for it rather than exploit it is found in many traditional cultures, but has been lost by some and land seen as a resource to be exploited, rather than stewarded. But landscape architects, by virtue of our training, are uniquely positioned to take the lead. We know that any landscape has many layers – of history, and of geography, and complex web of relationships – things that Professor Cabral pointed out to his students one of the many journeys they undertook - not as tourists, but as students of the landscape. By taking time to look, we can discover the secrets of a site, so that the solutions can be found which meet the need of all, and preserve what Cabral called “the general balance of nature”. We have more tools now than he did when he started out with his set square and watercolours. Geographic Information Systems (GIS) give us the ability to easily capture the physical features of a landscape – its gradient, vegetation cover, and built environment to name but three. We can build up maps showing the layers of data. We have our computers, and our LandSat pictures, and these are useful. Were Cabral here, I suspect he would remind us to step away from the monitor, and open our eyes. To learn how to acquire wisdom by looking. To see beyond the initial beauty of a landscape, to see its layers its whakapapa. If we look, we could see how the land evolved by the way humans use it. We can see that it can simultaneously be an economic resource for farmland or viniculture, a recreational space, and a water catchment area. We can see the effects of human activity, and the way the space has evolved. We may see the way different parts of the landscape connect, and how each is interdependent with each other. We may also see how people love it, and relate to it. Celeste Ramos wrote that

“Travelling with the professor .. had its “daring” aspects as he drove his Volkswagen 600 at more than 80 km an hour. At this speed no one but he spotted the Silene or Chrysanthemum on the sides of the road …. In language appropriate for children’s tales he would tell us what weeds we would find there and why, and how silly it was to have road-menders who every summer carefully stripped the kerbs and ditches of all plants they thought were useless and out of place but that without them the little creatures of the earth or the sky who fed on their leaves and flowers and fruit also disappeared. And so with the butterflies who visited these flowers and depended on them for their livelihood and even to display their wings in flight and land on these plants.”

In his teaching Cabral predated the nature movement in Britain where there is a move against mowing motorways. He was, in every sense a visionary. By contrast, too often around the world we see examples of a lack of foresight, the tendency to see individual areas in isolation. Weeds are removed without thought for the butterfly. A focus on short-term solutions, coupled with a lack of attention to planning, and a shortage of people with appropriate skills have taken their toll on many environments. Increased density of population is putting pressure on natural resources and many landscapes exhibit signs of stress. We need to remember, that one landscape must serve a variety of needs and perform a variety of functions. As Cabral taught his students to observe, multiple uses of landscapes have evolved over time, or by default. An urban park can be a sink, with trees and vegetation absorbing water and run off and preventing floods. But if the park is paved over, the planting decreased, the park can decline and other problems arise, of flooding, or pollution.

High Performance landscape

We are now seeing a movement in landscape architecture towards what are called “High Performance Landscapes”, a movement that is particularly strong in New York City, where the Design Trust has sponsored guidance protocols. In doing so, they follow in the thread of writings from landscape practitioners across the ages. More than forty years ago Cabral was writing about the need for a Manifold Landscape Design which could meet multiple purposes.

Shelter belt to love and peace

He gave the example of a shelter-belt, designed as a solution to provide protection from the wind. On the one hand

“You will in one case have single rows of eucalyptus or cypresses…where no bird will nest, no flower appear, and that after a short time begin to decline because they were not adapted to this particular landscape. “

On the other hand, you will have a well-balanced hedge with trees and shrubs, and at its border you will have in the Spring and Fall beautiful blooming annuals and perennials. The whole system will have plenty of life from the soil to the top of the highest tree. And men looking at this will think not only of wind-shield, that is very good, but also of beauty and love – which are even better. And this will be achieved without extra means, only because it was conceived and designed from the beginning to be so. This is the great job of the landscape architect in the near future. The task before us is to ensure that the landscape shall be again one – the town, the country and the factory – one in beauty, one in the collaboration of their functions and in the understanding of people that is the real foundation of Love and Peace among men.

As I said at the beginning of this speech, preparing to talk to you has been something of a voyage of discovery for me. I have had the chance to reflect on the way the world changes, and how some underlying principles do not change. I wish I had met IFLA’s fifth president, Professor Francisco Caldeira Cabral. His travels, or as he called them “studies” with his students encompassed much of Europe and parts of Africa. I think he would have enjoyed very much travelling with me in New Zealand, and seeing our landscapes, cataloguing our plants. It has been said that we see far only because we stand on the shoulders of giants. Francisco Caldeira Cabral was a giant of the landscape architecture profession, here in Portugal and world wide. Versed in art, science, and nature, blessed with determination, courage and the desire to learn he was a communicator, a teacher and a servant. I encourage you to follow in his footsteps, to travel, to look, to learn. Come and visit us in New Zealand and see our landscapes. As you travel, look at the landscape, look past the surfaces cluttered with advertising and look for what is underneath. Where-ever you travel, I encourage you to look deeply at landscapes, to seek to understand the natural process. For, whenever you seek to learn by looking, you take a step on his path When you speak truth to power, and stand up for stewardship, you take a step on his path. When you seek sustainable design solutions, drawing on the landscape itself and the needs and desires of the people, you travel on his path. When you seek to keep on learning, and sharing your learning with others, and seek to serve your profession and the world you follow in Cabral’s footsteps. When you study nature, practice your art, and allow yourself to connect spiritually to the landscape and to your work, and when you seek to serve others, in your profession, and in the global community you are following his journey. As landscape architects we are blessed with a rich inheritance, the capacity to do good, and plenty of opportunities to do it. Although we cannot do everything all at once we can each do something to make a difference. Professor Cabral had a motto : Festina Lente : Make haste slowly. Each step we take is insignificant in itself, but they all add up. Today we acknowledge his contribution, and commit ourselves to follow in his footsteps, remembering the adage he lived by: Festina Lente! In his words “The task before us is to ensure that the landscape shall be again one – the town, the country and the factory – one in beauty, one in the collaboration of their functions and in the understanding of people that is the real foundation of Love and Peace among men”.

References

1. Andreson p 33 2. See Appendix 3. Vasco Graca Moura, O Resot Sera, Ainda, Paisagem: And what is left, will it still be landscape? 4. Tuan, Y (1974) Topophilia: a study of environmental perception, attitudes and values, Prentice hall, New Jersey, USA.pp260.p4. 5. Ibid p93.